12 Dec Should I consider long-term preservation of my research microbes?

By Kyria Boundy-Mills

Curator, Phaff Yeast Culture Collection

University of California Davis, CA, USA

Researchers often ask microbe collection curators whether any of the microbes they have in their freezer could, or should, be preserved for future use in a formal repository such as a public culture collection. The best time to think about this issue is before the strains are isolated or generated, and the second-best time is right now. (Please don’t wait until after retirement…) With some small efforts by researchers such as a couple more pieces of information, and confirmed compliance with some regulations, the microbes can be much more useful for future research.

There are specific criteria used by repositories to decide whether a microbe should be preserved:

Important discoveries

- The microbe was cited in publications.

- The microbe has useful or scientifically important phenotypes or genotypes. Examples include classical spontaneous mutations, or ability to produce valuable metabolites.

Investment in data

- Time and/or money were invested to generate genotype or phenotype data. Examples include genome sequence or metabolomics profiles.

- The classical phenotype tests used to identify yeasts before ribosomal sequencing was available are now gold mines for commercially valuable properties such as feedstock utilization and stress tolerance.

Immediate access would be needed

- Time is of the essence during public health emergencies. A classic example is the Zika virus samples preserved at ATCC which allowed rapid identification during the 2015 outbreak in Brazil.

Costly or impossible to replace

- Some microbes would be very difficult to replace, the equivalent of “moon rocks”, such as microbes from remote or extreme environments: deep sea vents, glacial ice cores, or endangered plant or animal species.

- Some would be impossible to replace, such as microbes from a habitat that has since been destroyed by development or climate change, or microbes isolated from now extinct species.

- Historic collections allow researchers to build on past discoveries. In addition, strains isolated before 2014 may not have Nagoya Protocol restrictions (see below).

Filling gaps

- Collection curators know the gaps in their collections, what types of specimens are in high demand, and how demand has changed over the years. A collection may desire to acquire specimens that fill gaps such as undescribed species, or a new geographic or host material sources of a given species. And don’t forget temporal diversity! Examples of uses of Phaff collection yeasts include the same yeast species isolated before vs. after climate change, and crop-associated yeasts isolated many decades ago vs. after common use of agricultural fungicides.

In addition, individual collections have policies and priorities that impact what specimens they prefer, and which they avoid:

Regulatory compliance:

- Researchers are encouraged to maintain records of the country of origin of each microbe strain, and the date a microbe was isolated. Here’s why: the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Nagoya Protocol (NP) established that each country owns its genetic material, and deserves a share of benefits such as royalties on commercial technologies developed using that genetic material. NP legislation for each country is available on the CBD website. Researchers outside that country (even in the US!) still must comply with that country’s legislation, especially for commercial use. Critical information to evaluate compliance with a country’s Nagoya Protocol legislation include the country of origin, and the dates the host material was collected and the microorganism was isolated.

- Researchers must comply with all relevant regulations, such as proper collecting permits and other documents. For example, the US National Park Service requires prior approval before collecting any specimens including microbes.

- Culture collections must comply with biosafety and biosecurity regulations. Researchers should know the biosafety level of each microbe strain in their freezer, and should make sure the culture collection they are contacting is notified of any human, plant or animal pathogens.

- Before depositing any microbes in a public collection, researchers should check whether any microbes have restrictions on sending them to a third party. For example, if the researcher acquired the microbe from another collection, many culture collections have Terms of Use that do not allow researchers to distribute those microbes to third parties. Another example: companies may share proprietary materials with a researcher under the condition that they are not sent to third parties.

Collection policies and preferences:

- Many culture collections have Deposit Agreements and/or Deposit Forms that detail conditions for receiving strains, and what associated information is required or requested. For example, the Phaff Yeast Culture Collection forms are available here. Because the Phaff collection is a biodiversity collection, consisting of wild-type yeasts, any GMO strains or lab strains are of low interest. Human, plant, and animal pathogens are of low interest due to low demand and extra biosafety and biosecurity responsibilities. On the other hand, microbes isolated from food and agriculture sources are of high interest to Phaff collection users.

So – to answer the original question:

Yes, researchers should consider depositing microbes in a public repository. Here’s some information to guide the process:

- First, find an appropriate repository. Microbe collections that preserve a broad variety of microbes are listed in the USCCN culture collection registry and the WDCM ccINFO website.

- Contact the curator to discuss yeasts strains and research priorities, and to learn what types of materials and data are valuable to that collection’s users. Side benefit: the collection curator may provide information on strains and data that can further your existing research projects or lead to new projects.

- Find out what information and documents that collection requires. Many collections have deposit forms and strain information worksheets or spreadsheets, to ensure they receive information that is required or useful for that collection and its user community, such as copies of collecting permits. For example, the Phaff collection’s Strain Deposit Worksheet is color-coded for required, requested, and optional information. This information helps the collection curator comply with regulations and meet the needs of current and future users of the collection.

- In future, when generating or isolating new microbes, make sure to document appropriate strain information to streamline future strain deposits.

Future generations of scientists that use these materials will be grateful for your diligence and generosity!

And here is one example of a successful transfer story, in pictures:

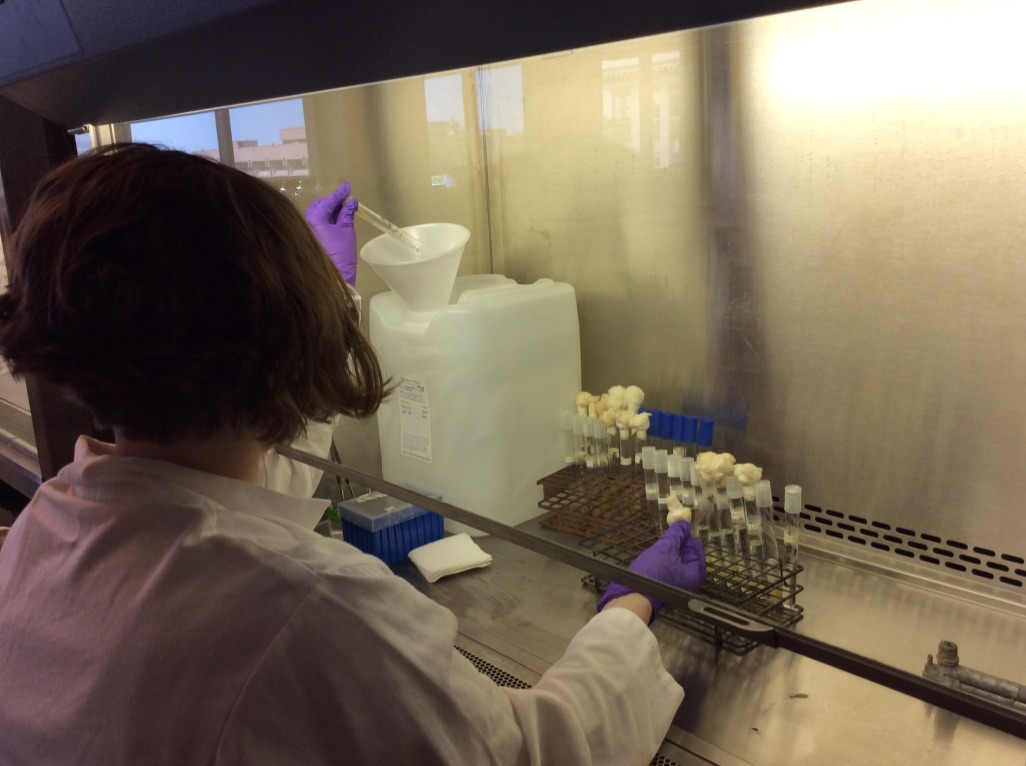

In 2026, Emeritus Professor W. T. Starmer from Syracuse University transferred his extensive collection of over 2,000 yeast strains to the Phaff Yeast Culture Collection at UC Davis. Dr. Boundy-Mills, along with technicians Russell Fry and Erin Cathcart, collaborated with Dr. Starmer to carefully pack and ship the yeast strains from New York to California. Each tube was filled with mineral oil to prevent the yeast stocks from drying out, and the oil had to be aseptically drained before shipping. Accompanying the yeast collection were Dr. Starmer’s original field notebooks, documenting the geographic origins and dates of isolation for each strain. These records are useful for many reasons, including ecology, phylogenomics, and compliance with the Nagoya Protocol.

- Phaff Yeast Culture Collection curator Boundy-Mills and Emeritus Professor W. T. Starmer of Syracuse University

- Boundy-Mills, Fry, Starmer, Cathcart.

- Original field notebooks kept by Dr. Starmer